Fieldwork Methods, Fall 2023: A Mini-Conference

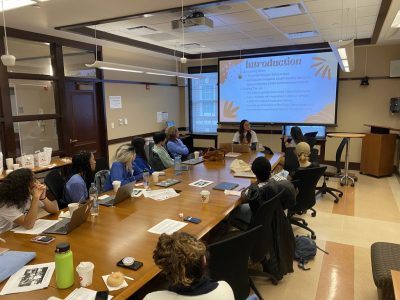

The Cultural Anthropology “Fieldwork Methods” class, a core requirement for the major, shone a spotlight on the ways that Cultural Anthropology holds space for students to explore their intellectual vision. On Wednesday, December 7th, 2022, Professor Katya Wesolowski held a mock American Anthropological Association (AAA) conference as a culminating feature of the course. Each of the students worked on semester-long ethnographic research projects, presented their findings in front of peers and graduate CulAnth students. These projects emerged from varied field sites, including medical schools, food trucks, engineering labs. They demonstrated how cultural anthropology offers an exciting and applicable perspective for students with a diverse set of interests.

The conference had 6 panels, each with 2-3 students whose projects shared similar subjects or field sites. The first panel, “Chew on This: Constructing Authenticity in the Triangle’s Foodie Culture'', investigated authenticity and culture in relation to different forms of food and drink consumption in the Triangle. One panelist studied Food Truck culture at Duke, and the other studied a Taiwanese Boba Tea shop in Chapel Hill. Both students spent many hours at their respective field sites, immersing themselves in the spaces. They gathered data on how food and drink can offer an authentic cultural experience, and how this experience impacts both the producer and the consumer. The Boba Tea shop study also discussed the ways in which commodification of Taiwanese culture gets mobilized as a tool to appeal to customers. Through close ethnography, the students offered compelling findings on “foodie culture” at Duke and the broader Triangle area, and what this culture reveals about authenticity as a feature of consumption.

The next panel of 4 students, “Student Socialization: Constructing Professional and Political Subjectivities,” focused on culture in medical, engineering, and political student spaces. It showed how different kinds of “professionalization and politicization” practices manifest within these spaces. The first study was a joint project between two students that analyzed the impact of curricular reform on students in medical school. Their findings suggested that in order to succeed and feel confident in their knowledge of healthcare, medical students need strong support systems, as well as to ensure that their levels of empathy do not diminish with increased stress-levels. The next study, shifting from medical to political investigation, investigated the motivations behind how college students decide to settle their views on abortion. The student researcher found that expressions of morality and religion allow students to make sense of these decisions, rather than conflict with them. The final project in this panel explored a Duke-student run engineering organization, Project Tadpole. Project Tadpole modifies toys for physically disabled children, and this ethnography of Project Tadpole used it as a case study to better understand engineering students’ attitudes towards disability. The researcher found that although extracurriculars like Project Tadpole provide a space for student engineers to expand their knowledge and understanding of disability, there is still room for more to be done on a larger scale. Focused on student beliefs and behaviors in three prominent fields–medicine, politics, and engineering—the panelists mobilized ethnography to answer pressing social questions.

The next panel, “An Ethnographic Look at the Changing Social Dynamics of Subcultures,” showcased students who studied how social groups develop community and inclusivity through activities at the margins of the mainstream. One panelist studied the Cosplaying community in North Carolina, and researched how societal norms and stereotypes play a role on inclusivity. The student presented their findings through a makeshift “Guide to Becoming a Cosplayer,” providing step-by-step instructions to cosplaying. The “guide” also concludes that although inclusivity is a shared goal among the cosplaying community, discriminatory practices still take place on several levels, and there are individuals within the community leading efforts to eliminate them. The other panelist in this group studied Durham's local Manifest Skate Shop, a site that functions as one of the city’s main hubs for skateboarders. The research illustrated how actively involved the community is in town hall meetings, and how they make decisions on the use physical spaces, such as mobilizing a petition for a new skate park. This panel addressed two very distinct subcultures, but drew important comparisons about expressions of community.

The fourth panel, “Gender in Motion: An Exploration of Weighlifting and Dance at Duke,” presented on gender dynamics and movement, through two ethnographic studies of Duke’s Swing Dance Team, and of the weight room in the popular campus gym, Wilson. The student researching the weight room addressed stereotypes that are reinforced in the space, and explained similarities between gendered workouts and socially mediated workouts, where “men’s upper body size is glamorized, while women’s lower bodies are oversexualized.” The student exploring Duke Swing also addressed stereotypical gender roles through attention to the roles of the “Lead” or “Follow.” They noted that there has been some progress in the use of language, as these terms were previously referred to as “Boy” and “Girl.” This panelist also made a striking point that although women are sometimes seen taking up “Lead” roles, men have essentially never taken “Follow” roles at Duke Swing. Through ethnography, this panel revealed how leisure activities that involve movement, such as exercise and dance, can offer new points of view into the dynamism of gender.

Titled, “Town and Gown: Spaces at the Intersection of Duke and Durham,” the next panel aimed to understand how Duke students and Durham locals interact. The first ethnography studied the Nasher Museum, open to students and the public, and it focused on the assignment of value to different spaces within the museum. The panelist spoke of their own experiences as a Duke student throughout their presentation to explain the importance of “liminal spaces” that allow visitors to engage in ways that don’t necessarily have to do with the gallery experience, such as the café and store. The student also discussed how the opportunity for students to use their food points at the Nasher restaurant offers an experience of “elitism” for people who may otherwise not be able to afford it. Another panelist conducted their fieldwork at Durham’s Shooters, a bar well-known among Duke students. Here, the findings reveal a conflicting relationship between locals and students, as the bar has become “overrun” by Duke students. This panelist discussed that although bars like Shooters are spaces that seem to instill community and inclusion, they also function as sites of tension between locals and young college students. The last panelist’s fieldsite was a robotics startup company that remotely employs some Duke students. This student presented on what remote work has to offer for people and how Covid has shifted the tech industry’s operations. They also discussed some of the downsides that have come with remote work, such as awkward communication and lack of strong community-building. I was drawn to this project because it represented how ethnography can function even outside of a concrete “fieldsite.”

The final panel, “Worlds of Wellness: Building Relationships through Alternative Healing,” of which I was part, consisted of three ethnographic studies that explored different sites of therapy or wellness practices. My project was conducted at Duke’s Puppy Kindergarten, where I investigated how dogs function as vectors of well-being, and human-canine interactions as sites of power. I discussed how the Puppy Kindergarten gave students an opportunity to relieve their stress, and how it is space where people assume authority over puppies and over each other, depending on whether they are a volunteer or a visitor. One of my fellow panelists conducted their fieldwork at two different sites where music is used as a healing device for children with developmental disabilities, and, in a different location, for elderly people living in a retirement community. Through her presentation, this student emphasized how useful of a tool music can be in providing therapy for people of all ages. The last panelist studied wellness on a broader scale, conducting her fieldwork at DuWell. She studied how the center functions as a “negotiator” between dominant and subdominant social groups, a concept that I found quite enjoyable. In this panel, we all studied different dimensions of wellness and social interactions, finding that people find comfort and community in alternative forms of therapy.

After each panel presentation, a CulAnth graduate student commented on each of the projects and posed questions to the panelists. This gave the experience a formal conference feel, and we enjoyed hearing about the graduates students’ fieldwork. This course, and the CulAnth major as a whole, provides students a chance to explore their interests, whatever they be, very intimately through ethnographic practices. Learning how to conduct fieldwork has been incredibly valuable, and it has encouraged me and many of my peers to move forward with writing a senior thesis. The conference allowed us to dip our feet into the professional world of Cultural Anthropology, and only reaffirmed my decision to pursue it as a major